Attachment:

imgJF2.jpg [ 39.44 KiB | Viewed 3953 times ]

imgJF2.jpg [ 39.44 KiB | Viewed 3953 times ]

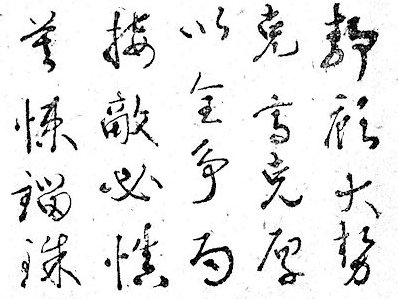

Quietly survey the entire position.

High is good; thick is good.

Stay whole as you fight your ground.

Once in contact with the enemy, be sure to be prudent.

Do not shy away from scruples and grains.One of the questions I am most asked is how much Sun Zi’s

Art of War is referred to in go. The answer is hardly at all. There is, of course, the

Go Classic in Thirteen Chapters, at least as old as the 12th century, which not only quotes

Art of War extensively but models its structure on it. But it cannot be gainsaid that otherwise references are thin on the ground.

So the typical follow-up question (it’s usually from someone who has believed the business-school hype about

Art of War being the book that gives access to the executive loo) is a baffled “why?”

It seems obvious to me. It’s not very useful to a pro. Leaving aside the different purpose and context of the original, not to mention the lack of evidence that Sun Zi would ever have made 9-dan pro himself, the book is just too woolly. A pro, soldier or go player, doesn’t need general advice on avoiding swampy ground. He needs specific intelligence for a precise next move. Sun Zi doesn’t do precision.

That said, there is apparently a huge market for dollops of general advice that promise instant business success, sex appeal or shodan without having to do any real work, and it seems to me that the amateur go world has swelled their numbers, east and west.

Armed with that frame of mind, my attention has just been caught by the message above. As far as I know it’s not by anyone famous (the calligrapher was Imamura Rikisaburo) and I don’t know the full story behind it. I have inferred that it was commissioned by an amateur around 1940 who was rather taken by the teachings of Onoda Chiyotaro 8-dan. I think this amateur probably dictated the text to be written by a professional calligrapher.

There are many interesting stories written about Onoda (I have mentioned a few in the various books I have done). One, from the timing, possibly relevant to the reason for commissioning the above is that he set a record for winning two consecutive Oteai sessions with perfect scores. This was in 1942 and 1943 Before that, though, he had played a game in the Oteai which would give him promotion to 7-dan if he won. He was playing a 4-dan who, presumably out of humanity or respect, resigned early, but Onoda refused to accept that. He said the game was far from over. Unfortunately, when the continued game was over, he found he had lost by one point, and so missed his promotion. What I like about the story, though, is that he did not then affect an air of superior dignity and humility. Instead he was truly humble enough (and he proved his integrity in many other ways) to regret his action, and the next day he shaved his head as a penance.

I think you can see already that such a man would be popular with amateurs, and our text confirms that. Onoda was wont to say that amateurs can’t (or won’t) read deeply but what they can do just as easily as pros is to take a moment before every move and, with a quiet heart, survey the whole position. That is what the first line tells us.

The second line is useful advice if you are an amateur playing by feel: high positions and thick positions are generally safe positions. You are disengaged from the enemy, so the need to read is reduced.

The third line is similarly useful, but raises some complex points. First, it is almost certainly an allusion to Art of War, but with a slight tweak to make it more relevant to go. The

Art of War has the phrase 以全争天下, i.e. with ‘empire/world’ instead of the ‘overall position’, or as I have put it ‘your ground’. However, a problem here is that no-one is quite sure what Sun Zi meant, though you’d never guess so from the confident versions of translators writing for the loo-key seekers’ market. Broadly, there are those who take the original as advice to strive to capture the empire ‘whole’ (the key word is 全). There are also those – I’d judge them to be in the majority, especially in Japan – who take it to mean that when you are fighting for the empire you need to keep your own positions whole. I’m certain that is what is meant here – keep your positions high and connected with access to the centre. (For completeness, there are other, quirkier interpretations of Sun Zi’s original, e.g. with 全 taken to mean ‘perseverance’). At any rate, this is advice an amateur persevering in his efforts to avoid thinking can easily and totally connect with!

We can take the second and third lines to cover the opening (the first is all-encompassing advice), and then the fourth line of the text deals with the middle game and the last line with the endgame. The fourth line is trite, perhaps, but Onoda would remind pupils to take care even in an obvious-looking ladder. Line 1 still applies!

The last line essentially means you must count the value of endgame moves before you play – something amateurs can do tolerably well and easily, although we all know that the only purpose of any move by many amateurs is to get to the next game as quickly as possible. The phrase 錙銖 is just a posh way of saying 細かい and is built up from words meaning ‘scruple’ and ‘grain’ – in the historical senses. I’m inclined to believe we can detect here a grain of despair from Onoda as he urged his amateur pupils over and over again to count.

Overall I think we can treat this whole message as an amateur’s licence to play the way he clearly prefers – without thinking – so long as a modicum of common sense, as prescribed here, is applied. In fact I know a 4-dan American taught to play in just such a manner by a Korea. He played pretty fast but never blitz and was very successful. It seems that it took players of 4-dan and upwards to combat this style of play. Below that, opponents were just plain flummoxed as they had nothing to get hold of.

A word on the calligraphy. I take it to be by a professional calligrapher, not just because of the generally neat and distinctive style but because the strokes match the thoughts. The most important word, because it is the only one that allows us to follow the rest of the advice sensibly, is the first one: quiet. This has the heaviest strokes by far. Of course it is written when the brush is still full of ink, but that mirrors our feelings of passion as we prepare to play the next move. Also the character for ‘prudence’ (慎) is emphasised with heavier strokes. In contrast, the two characters for ‘scruple’ and ‘grain’ are written with the lightest of touches. Note also the way the important character 全 is highlighted by being raised.

For those who need it, the printed form of the text would be:

静顧大勢

克高克厚

以全争局

接敵必慎

無悚錙銖